They're wrong: given almost any statement you can find some people who agree, and some who do not, that doesn't make nearly everything subjective (delighted as the relativist would be by this conclusion). There are people who think that the earth is flat, there are some who think it is roughly spherical. The topological nature of the earth does not therefore become a subjective matter! The disagreement is not a sign that the answer is merely a matter of opinion, instead it is a sign that some people are wrong. Similarly if everyone on earth agreed that strawberries tasted nicer than raspberries (a scenario that can easily be obtained by killing everyone with a differing view) this would not become an objective matter, it is merely a subjective matter on which there is a consensus.

What then do these terms actually mean? The clue is in the name. Here a brief diversion into the structure of language is required.

In sentence a verb usually takes a subject (the thing doing the action) and an object (the thing the action is being done to). So for example in the sentence "I like the colour blue" I am the subject, the colour red is the object (like is a verb). Now let's carry this knowledge back to our question.

If some property is objective then it is a property of the object only. For example if I say 'this pen is 7 inches long' then this is a statement about the object only. If a property is subjective then it is determined not by the object alone, but also by the subject. So if I say 'Strawberries taste better than raspberries' I am actually making a statement not just about strawberries and raspberries but also about myself. You see 'Strawberries taste better than raspberries' is just a shorthand for 'I prefer the taste of strawberries to the taste of raspberries' - it is not just about soft fruit, it is also about me.

We are now in a position to define these terms formally:

A proposition is objective if its truth depends purely on the object under study. A proposition is subjective if its truth depends not merely on the object alone, but also on the observer and the relationship between the two.

There are a few immeadiate consequences to our proper understanding of these terms which it is worth drawing out:

- For every subjective proposition there is a naturally equivalent objective one: we simply extend the object under study to include the observer and the relationship between the observer and the original object. So for example although the statement 'Strawberries taste better than raspberries' is subjective, the statement 'Neil prefers the taste of strawberries to that of raspberries' is objective.

- Being subjective does not neccessarily make the propsition in question an uninteresting one. For example whether a given meal prepared in a restaurant tastes good or not is a subjective matter - it isn't a question which makes sense without introducing a subject - the eater - it is still well worth a chef paying attention to his customers (albeit subjective) views on the taste of his dishes, and adapting his cooking accordingly.

I have come across several people who feel the need to defend their work by saying 'this isn't subjective' (for example ' 'asthetics aren't subjective' or 'good user interface isn't subjective'). They are wrong of course, they are clear cut examples of subjective matters, but also matters on which there is a strong consensus, and so a useful study can be made of them.

Source: http://pinkstuff.publication.org.uk/~neil/RelPhil/SubObj.html

1. objective Facts

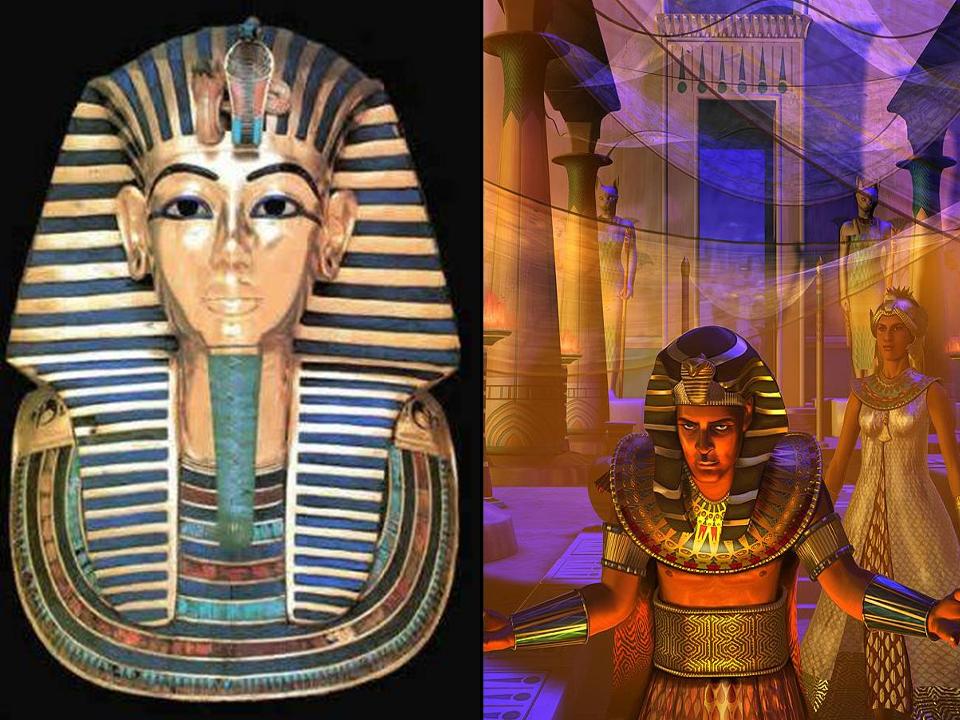

EX.PHARAOH

The most powerful person in ancient Egypt was the pharaoh. The pharaoh was the political and religious leader of the Egyptian people, holding the titles: 'Lord of the Two Lands' and 'High Priest of Every Temple'.

As 'Lord of the Two Lands' the pharaoh was the ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt. He owned all of the land, made laws, collected taxes, and defended Egypt against foreigners.

As 'High Priest of Every Temple', the pharaoh represented the gods on Earth. He performed rituals and built temples to honour the gods.

Many pharaohs went to war when their land was threatened or when they wanted to control foreign lands. If the pharaoh won the battle, the conquered people had to recognise the Egyptian pharaoh as their ruler and offer him the finest and most valuable goods from their land.

Subjective Opinions

EX:An exchange on musicians and music critics

Are musicians and sabhas thin-skinned, intolerant of criticism? Are The Hindu's music critics doing a good job?

I was extremely intrigued by the comments of Mr. N. Ram published on the 28th of February in The Hindu regarding critics and musicians during a recent function in Chennai. While he has been quite scathing in his criticism of musicians, saying that we are thin-skinned and want only favourable reviews, it is quite sad to note that there has been absolutely no self-introspection in his speech about the quality of critics in The Hindu. Barring a few critics, I can say as a student of this art form that the knowledge of the critics today is abysmal. It is not about understanding very complex technicalities, even at a very necessary level it is lacking. I can back this with numerous reviews published in The Hindu itself.

The situation during the music season is even funnier. Suddenly a dozen people who don't write through the year appear and start writing reviews. Often the reviews are only reports and any semblance of criticism is very mediocre. Let me even say that many reviews of even mine, which have been lavish in praise, have been extremely poor in content and quality.

Therefore it is not about only negative reviews; even positive reviews are bad. Some critics find it necessary to display their knowledge of music by trying to quote some technical aspects like derivatives of the raga etc while the real lack of musical acumen is very evident. Therefore while there are musicians who have not accepted harsh criticism there is also that the fact that The Hindu can no longer believe that its reviewers are of a quality to be respected. Comparing this with the detail and knowledge expressed in a review in, say, The New York Times is totally wrong.

Let me add that Mr. S.V.K. [S.V. Krishnamurthy, The Hindu's chief music critic], for whom this function was held, is a very rare breed. I have myself received both positive and negative reviews from him but never has this affected our relationship. There are people who have completely disagreed with him but we all know that his opinions are based on his personal perspective backed by knowledge of music.

While I will be the first to accept that we musicians are not an easy lot and do find it difficult to accept criticism I think there is also an urgent need for The Hindu to introspect on what the qualities of a critic should be and how they select the same.

No amount of guidelines will help unless the right people are found. I completely agree that robust criticism is very necessary but it can be robust only when people are chosen very carefully and at the same time I do agree that musicians need to understand the role of critics. But one is not going to happen without the other.

T.M. Krishna, Carnatic classical musician

N. Ram, Editor-in-Chief, The Hindu, comments:

T.M. Krishna is a very fine musician with a deep knowledge of Carnatic music. We have had interesting and useful interactions with him on various subjects. But evaluating music criticism is not his strong suit — judging from the condescending tone of this polemical response and his sweeping dismissal of the competence of our music critics. He enters some caveats in his polemic but his attitude is like that of a successful Test cricketer dismissing reportage and critical assessments by cricket writers by asking: ‘What does he know about playing in the middle? Has he played first division, let alone first class cricket, not to mention Test cricket?'

We and tens of thousands of our readers, knowledgeable as well as lay (like me), think highly of our critics, most of whom are well schooled in Carnatic music or are experts. The majority of them, in fact, are not staff journalists.

Mr. Krishna's forthcomingness is useful because it illustrates the very point I made at the felicitation function mentioned above and have been making generally over the music season — because it is a long-observed problem that needs to be faced squarely and resolved. If his sweeping and dismissive opinion of our music critics as a group can be said to be representative of the opinion and attitude of professional musicians (and sabhas) to music critics as a fraternity, it is certainly a problem of being either condescending or thin-skinned or both.

My critical observation, which “extremely intrigued” Mr. Krishna, drew explicitly from “What The Hindu expects from its music critics: Some guidelines” — guidelines we adopted some years ago in consultation with our music critics, which have been continually revised. The document can be read at www.thehindu.com.

Para 10 of the Guidelines reads: “Finally, the critic is an individual expert rasika, and writer on music. We know that many musicians and sabhas are extremely thin-skinned. They are not used to the robust and, at times, fierce criticism musicians in western countries get all the time (whether they like it or not). Our musicians and sabhas want only favourable reviews but that is decidedly not The Hindu's expectation. We choose our critics and respect their musical knowledge, their integrity, their independence of judgment, and their writing style. It is your review and we know a subjective element forms part of this. It does not matter if you are alone in your musical judgment — as long as you make clear to readers the basis of this judgment, write insightfully, fairly, and interestingly, and comply with our deadline and word length requirements.”

While thanking Mr. Krishna for taking the trouble to respond to this criticism, we leave the matter for readers to judge.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น